The Bihar election is being seen as a referendum on Nitish Kumar and his slogan of sushasan or good governance. With the cracks beginning to show days ahead of the first phase of polling for the Bihar Assembly elections, we listen to voices on the ground to see what stands between Nitish and a possible fourth term.

Nitish Kumar ko gussa kyon aata hai (why does Nitish Kumar get angry)? Last week, as the Bihar Chief Minister and JD(U) chief lost his cool at a jeering crowd during a rally in Saran, that’s the question many asked — and, in politically astute Bihar, believed they had the answer to.

At the rally for party candidate Chandrika Rai, the estranged father-in-law of the RJD’s Tej Pratap Yadav, as a section of the crowd raised ‘Lalu zindabad’ slogans, Nitish Kumar snapped: “Vote nahin dena hai to mat do, lekin yahan se chale jao (If you do not want to vote for us, it is ok, but leave.”

It was a sign, many deduced, that the ground was shifting beneath the feet of the three-time CM. Yet others saw in his rage the impatience of a man who has towered over the last two Assembly elections as the larger-than-life CM face — first of the NDA in 2010, and later with the Grand Alliance in 2015.

As Nitish bids for a record fourth term as CM, what’s clear, though, is that politics has come full circle for the man who had kept then Gujarat CM Narendra Modi out of Bihar during the 2009 Lok Sabha and the 2010 Assembly polls campaigns in Bihar, despite being part of the NDA in both elections.

This election, though, it’s a different Nitish. On Friday, as he spoke at a rally in Sasaram on Friday, most cameras captured a telling shot. In the backdrop, framed against a diminutive Nitish, was a colossal poster of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. That Friday’s PM rallies at Sasaram, Gaya and Bhagalpur were telecast live in scores of NDA Assembly segments is another sign that past equations have changed, for better or worse.

Days ahead of the first of the three-phase elections starting October 28, The Sunday Express looks at what’s working on the ground for Nitish, what’s not? What are the challenges as he aims for a fourth shot at chief ministership?

Election wide open

In a year of deep economic distress compounded by Covid, Nitish Kumar bears the burden of being the incumbent. Yet, his past record of allying both with the NDA and the Mahagathbandhan, along with the LJP factor, mean that this is an election wide open.

Anti-incumbency, sense of fatigue

“In his three terms, Nitish Kumar has given us three basic things — roads, drinking water and electricity. Now he wants another term to give water to every field. Will he need another 50 years to create jobs and check migration?,” sniggers Narendra Pathak of Khairihi village that’s part of the Dinara Assembly. He had voted JD(U) in the last election but says he is impressed with the LJP candidate this time.

It’s this growing impatience among voters with Nitish and his governance that defines this election.

From a state left languishing at the bottom of most charts, during Nitish’s 15 years as CM, Bihar grew steadily, clocking above-average growth rates, and increase in spending. Like Pathak, most concede that the Nitish regime has been largely corruption free, with improved law and order and public infrastructure (roads and bridges). Bihar recorded an average growth rate of over 11 per cent during the last 15 years, mainly because of growth in construction, telecommunication and other secondary and tertiary sectors.

Yet, Bihar remains plagued by problems such as minimal industrialisation and poor social indicators. At the end of 2016-17, only about 2,900 of Bihar’s estimated 3,531 factories were operational, employing on an average 40 people each, well below the national average of 77 workers.

Though many of these are legacy issues, along with that seemingly intractable problem of lack of jobs, most admit that his government’s “mismanagement” of the Covid crisis and handling of migrants who returned home have made his report card look worse than it is.

There is now a sense of deep hurt that Nitish did little as many of the migrants walked back home during the lockdown, and did nothing to hold them back once it was lifted.

“Over a hundred people returned to our village during the lockdown; they have all gone back to Gujarat. Under normal circumstances, they should have stayed back to cast their votes. But this time, they were not at all interested. Rather, they were upset with the way Nitish Kumar treated them,” says Pathak.

A JD(U) leader concedes that though Nitish Kumar had gone by Covid protocol when he told people from Bihar to stay where they were during the lockdown, UP CM Yogi Adityanath’s move to send buses to bring home UP migrants left workers from Bihar upset. “The impression was that their own CM did not want them to return home. That our government did not try to bring back stranded students from Kota also did not go down well. We did help migrants later but the sense of hurt remained somehow,” said the JD (U) leader.

Nitish does attempt to arrest the drift when, in his speeches, he comes up with minute details of what government did for Covid management and migrants’ welfare. In fact, he remembers most of the data by heart now — how the government’s testing of Covid samples per 10 lakh population is 3,000 more than national average; how Bihar’s recovery rate is above 90 per cent; that the government spent Rs 5,300 on each migrant during their stay at quarantine centres; about giving 5-kg rice and 1-kg pulse to every migrant family; how the government has done skill mapping of 17 lakh migrants; and is trying to give them jobs under central and state government schemes.

Yet, there are questions.

“What has he done for employment generation in the last 15 years? Did he try holding back the 40-lakh migrants who returned to Bihar? Some bottling plants and ethanol units had opened but they closed after the government decided to ban liquor,” says Umesh Singh, a Rajput voter from Jagdishpur in Bhojpur who has traditionally voted for the NDA candidate.

The problem for Nitish Kumar is that the narrative of economic distress seems to be entering segments that were once considered his bastions. For instance, in the reserved Phulwari constituency, in a Dalit basti at Parsa Bazaar, Dalit women — who had voted for Kumar in large numbers in 2015 enthused by his promise of prohibition and reservation at the panchayat level — now say the “government has forgotten the poor”.

They allege that prohibition exists only in name, with an underground economy ensuring illegal alcohol is sold at higher prices and worse, delivered at home. Says Mamta Devi, “At least earlier I could lock my husband out if he was drunk. Now he drinks at home.”

His critics point to the sense of fatigue in the administration, something RJD leader and the Opposition’s CM face Tejashwi Yadav has been quick to capitalise on with his “thak gaye Nitish Kumar (he is tired)” taunt.

The LJP factor: Distrust on the ground

Until July, the NDA looked formidable against the Grand Alliance that was caught up in its internal bickering. However, the first cracks began showing with LJP national president Chirag Paswan intensifying his attack against Nitish Kumar and walking out of the NDA. With that, the rival camp got its first opening.

That the BJP maintained a tacit silence as Paswan junior openly took on Kumar, all the while heaping praise on the BJP and Modi, left the JD(U) suspicious of its ally’s intent.

It was only after a caution from the JD(U) that the BJP criticised Chirag, backed Nitish and announced joint rallies of the Prime Minister and Kumar.

Despite their protestations, what is clear is that the JD(U) is up against a new front in the polls: the LJP factor.

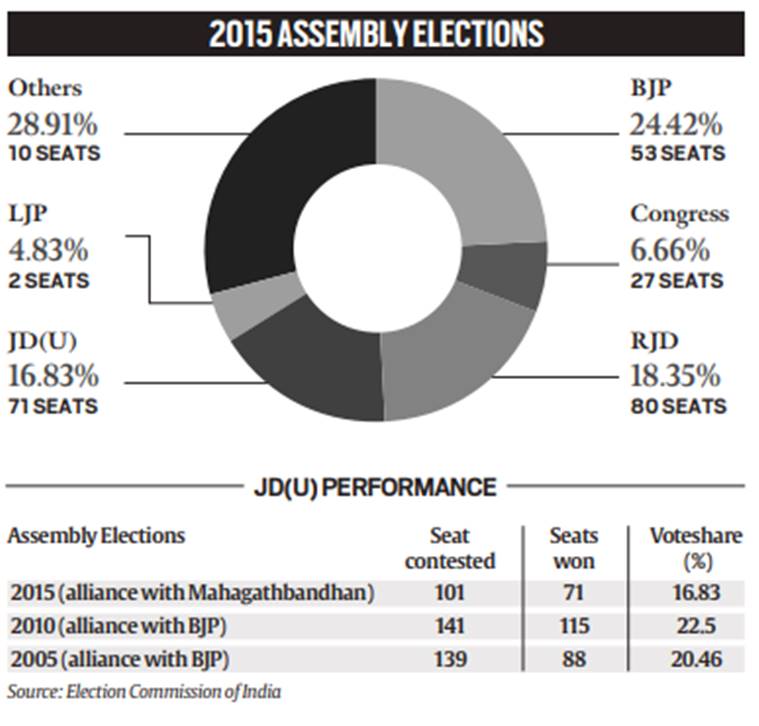

As a player that has commanded a vote share of between five to eight per cent, the LJP’s votes have the potential toplay spoilsport.

With the LJP, which is fighting on 143 seats, facing the BJP only on five of these, it is the JD(U) that will suffer from the LJP’s separation.

LJP spokesperson Ashraf Ansari said, “We can dent the JD(U)’s prospects on at least 20-25 seats as there will be at least 70-odd seats in this election where the victory margin could be less than 5,000. This is where the LJP will be a factor.”

At least a dozen BJP ‘rebels’, including Rajendra Singh (Dinara), Rameshwar Chourasia (Sasaram) and Dr Usha Vidyarthi (Paliganj), have crossed over to the LJP, leading to murmurs — and strong suspicion in the JD(U) camp — that they had been propped up by the BJP.

If the party ends up cutting into the JD(U) votes, as the LJP claims it will, the RJD could end up with more than a fighting chance in a number of seats.

Shashi Singh, a small businessman in Dinara town — where veteran BJP hand Rajendra Singh is now fighting on an LJP ticket — says, “The contest between LJP’s Rajendra Singh and JD(U)’s Jay .Kumar Singh might end up helping RJD candidate Vijay Kumar Mandal”

On the ground, the emergence of the LJP has led to deep distrust between JD(U) and BJP cadres.

Though Amit Shah and other top BJP leaders have reiterated that Nitish Kumar will be CM even if the BJP wins more seats than the JD(U), the impression of the LJP being a “plant” of the BJP or its “B team” has gone down the JD(U) ranks.

For instance, in Jamui, with Chirag announcing the LJP support to the BJP’s Shreyasi, most JD(U) leaders have been staying away from her campaign. There is no trace of JD(U) workers or their flags as Shreyasi’s campaign made its way through villages such as Bela, Dharampur, Chihutiya and Kairakado on Thursday.

A BJP worker said: “The JD(U) has become disinterested. They do not oppose us but do not come out in support either. LJP workers have been doing all the work. There is also a chance that JD(U) and LJP workers may clash so we are trying to avoid any unpleasant situation.”

The JD(U), however, believes that the onus is on the BJP to come out strongly and say clearly that they are with Nitish. “They are trying to disown the LJP but have not done it fully. Amit Shah recently said they would take any decision on whether LJP is an ally at Centre or not after polls. There needs to be greater clarity on this.”

So far, the RJD has been emboldened by the huge crowds that have been turning up at Tejashwi Yadav’s rallies, with his promise of 10 lakh government jobs drawing the loudest cheers. The party also hopes the LJP factor will see it ending up in a comfortable position post elections.

Under Tejashwi, the RJD has shed the party’s old slogan of “secularism and social justice” and worked on a new development theme.

An RJD leader said, “When we found there were 4.5 lakh pending vacancies in the Bihar government and need to create another 5.5 lakh vacancies to match the national average, we came up with the idea of 10 lakh jobs. Now the BJP is trying to copy us. Call it populism or whatever, it has hit a chord with the common man.”

So far, the RJD has been trying to beat Nitish at his own ‘development’ game. In contrast, the JD(U)’s vision document,

Saat Nischay-II, has so far failed to catch popular imagination.

Says Satish Kumar of Karahgar Assembly segment, “Nitish has raised the ‘Lalu raj’ for far too long. The return of Yadav raj is the only thing that’s holding back some voters, but Tejashwi has shown promise. This is a 2020 match and will go down to the wire.”

Social math may work in Nitish’s favour

Despite anti-incumbency and unfavourable voices from the ground, the NDA is pinning its hopes on Bihar’s tried and tested social math to take it past the winning line. Over the past 20 years, there have emerged in Bihar three political poles, each broadly holding on to a section of the community.

The BJP has upper castes, Bhumihars, and a section of non-Yadav OBCs; JD(U) has the lower castes, Mahadalits and EBCs; and the RJD has Muslims and Yadavs.

The common consensus has been that when two of the three poles come together, there is very little chance for the third to win. In 2010, it was the JD(U) and BJP, and in 2015, JD(U) and RJD.

JD(U) analysts told The Indian Express that there were three factors that leave them confident of a win. “One, that this social mathematics gives us at least a 10-12 percentage lead. That is too big to overcome. Second, despite everything, many will still not see a viable alternative to Nitish Kumar and, despite being angry, may still vote for him. Tejashwi has no experience and people know him as someone who failed Class 9. Third, they know the jungle raj pre 2005. I am not saying there is no anger. I am saying that it is infinitely better than in 2005,” the JD(U) leader said.

The game, then, is still wide open.

0 Comments